Chronic pain program provides model for small practices

New laws in Kentucky meant to curb opioid misuse were drafted from the standpoint of law enforcement and not medical practice, leading to areas of confusion for clinicians and their staff. ACP created a model that practices could follow to improve care for patients.

Where: 8 primary care practices in Kentucky.

The issue: Improving the safe and effective treatment of chronic pain.

Background

In April 2012, Kentucky passed legislation designed to help prevent abuse, misuse, and diversion of controlled substances. But the new law, and the regulations developed in order to comply with it, were drafted from the standpoint of law enforcement and not medical practice, leading to areas of confusion. “The law was internally self-contradictory on a number of points and made it extremely difficult for physicians to know what to do,” said Gregory Hood, MD, MACP, a former Governor for ACP's Kentucky Chapter.

For example, when initially announced, the law and regulations specifically pertained to the brand-name versions of certain controlled medications but not their generic equivalents. In addition, the law as enacted in July 2012 was very broad and, as the legislator who introduced it later admitted, not consistent with state medical board regulations, Dr. Hood said. Both the law and board regulations underwent amendments, and consequently primary care practices across the state were profoundly confused about how to comply, he said.

To help physicians implement the new rules and improve their chronic pain management practices, ACP and its Kentucky Chapter collaborated on the ACP Quality Connect: Chronic Pain Management initiative, a quality improvement pilot program.

How it works

The pilot project began in May 2014 and involved 8 practices, each of which was part of an accountable care organization or working toward designation as a patient-centered medical home in an urban, suburban, or rural setting. Half of the practices were solo private primary care practices; only 1 practice had more than 10 physicians.

To kick off the project, said Dr. Hood, its lead investigator, ACP representatives met as a group with the program champions, a physician and nonphysician representative from each participating practice. Nonphysician champions were included in the discussions to ensure that the program design would address top educational and quality improvement priorities for the entire office staff, said Dr. Hood.

“We had a face-to-face meeting with these people, talked about the nature of the problem, the barriers, the opportunities, and where some of the national literature was showing weaknesses and opportunities, as well as what the specific restrictions [of] Kentucky regulations meant for the practices,” Dr. Hood said. He gave a presentation on the new legislation, and other experts gave presentations on chronic pain management and quality improvement.

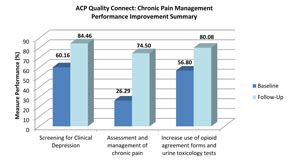

The project's advisory group decided that all participating practices would work on improving a core set of measures: screening for clinical depression, assessing and managing chronic pain, and increasing use of opioid agreement forms and urine toxicology tests. Each practice's physician champion used the ACP Quality Connect: Chronic Pain Management Practice Assessment Tool to assess background, quality improvement experience and capacity, and current chronic pain management strategies.

To help the practices improve, ACP quality improvement leaders performed practice site visits where they reviewed practice workflow, provided an overview of quality improvement processes, and established quality improvement teams. The physician and nonphysician champions from each practice also received regular coaching calls from an ACP quality improvement expert.

Practices participated in 2 CME-certified webinars on pain/mental health assessments and pain contracts/risk assessments and received access to educational resources, including patient education brochures, webinar recordings, quality improvement videos on chronic pain management, and the ACP Practice Advisor. A grant from Pfizer provided some remuneration for practices as they took on the extra work.

Each participating physician provided data for 25 adult chronic pain patients at baseline and at follow-up in December 2014. The impact of the program on clinicians' rates of screening for clinical depression, assessing and managing chronic pain, and increasing use of opioid agreement forms and urine toxicology tests was assessed by comparing these measures at baseline and at follow-up.

Results

Use of the 3 measures varied extensively by practice at baseline but applied to most patients in all but 1 of the 8 practices at follow-up. Sixty percent of patients at baseline and 84% of patients in the post-program period received depression screening, use of a pain assessment increased from 26% to 75% of patients, and use of opioid agreements and urine toxicology tests increased from 57% to 80%.

“One thing that is notable is the practices were energized about doing this,” Dr. Hood said. “We had much higher engagement throughout the program than one might typically expect in working with such a heavy subject matter.”

Challenges

Practices varied greatly in their previous experience doing quality improvement. Without this project, they would have had to seek out other resources to help them comply with the new laws and regulations, which might not have been as effective, Dr. Hood said. “Clearing up potential misperceptions, making sure they really understand the letter as well as the intent of what the regulations can mean in terms of complications, is just a really critical element,” he noted.

Next steps

The overwhelming success of this initiative in Kentucky has provided a blueprint for ACP's quality improvement programs moving forward, Dr. Hood said.

“We are hoping to expand this style of program to different ACP chapters, and the overall style and structure can be much the same, but the content will need to be adapted due to the state-by-state differences in the rules that govern our prescribing,” Dr. Hood said. “We also hope to do some follow-up and further reevaluation with these practices of the approach to controlled substance prescribing.”